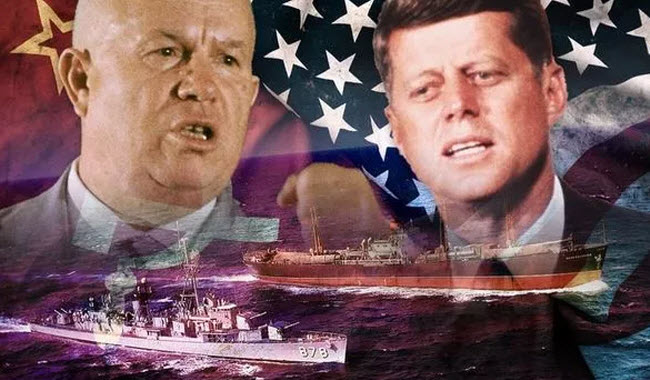

The Cuban Missile Crisis stands as one of the most pivotal moments in Earth’s history, during which the world held its breath for 13 days, witnessing the looming threat of a third World War. This conflict was poised between former allies turned adversaries—the United States and the Soviet Union. October 1962 was one of the most perilous periods of the entire Cold War era, with both sides coming close to deploying nuclear weapons capable of obliterating all forms of life on Earth. The imminent clash between the two superpowers was the result of miscalculations, poor judgment, and inadequate communication during diplomatic exchanges and secret channels. The crisis was ultimately defused through timely corrections and concessions from both sides before it spiraled out of control.

The crisis unfolded following the failed attempt by the United States to overthrow Cuban revolutionary leader Fidel Castro during the Bay of Pigs invasion. As the Kennedy administration was planning Operation “Anadyr,” Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev reached a secret agreement with Castro in July 1962. Under this agreement, Soviet nuclear missiles were to be deployed in Cuba to deter any future American invasion. Construction of several missile sites began in late summer. However, the CIA uncovered evidence of Soviet weaponry, including IL-28 bombers, in Cuba through routine reconnaissance flights. On September 4, 1962, President Kennedy issued a general warning against introducing offensive weapons into Cuba. Despite the warning, on October 14, an American U-2 spy plane, piloted by Major Richard Heyser, captured photos clearly showing the construction of medium-range ballistic nuclear missile sites in Cuba alongside Soviet SS-4 missiles. Once these photos were analyzed and presented to decision-makers at the White House, the Cuban Missile Crisis began in earnest. The nuclear-armed missiles were positioned just 90 miles south of Florida, close to the U.S. mainland. From these launch sites, the Soviets would have had a significant advantage in reaching targets in the eastern U.S. if the missiles became operational, drastically altering the nuclear balance of power.

On the other hand, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev bet on sending these missiles to Cuba to enhance his country’s capability to deliver nuclear strikes, driven by Soviet concerns over the number of nuclear weapons targeting them from Western Europe and Turkey. The Soviets saw the deployment of missiles in Cuba as the easiest way to achieve parity.

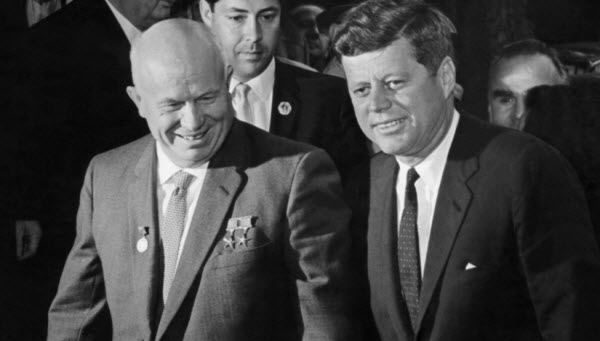

President Kennedy convened his closest advisors, known as the Executive Committee or “ExComm,” to review options and guide U.S. action to resolve the crisis. There was debate among advisors, with some advocating for air strikes to destroy the missile sites followed by a full-scale invasion of Cuba. Others preferred issuing stern warnings to both Cuba and the Soviet Union. The meetings concluded with Kennedy opting for a middle ground. On October 22, he ordered a naval quarantine of Cuba, carefully choosing the term “quarantine” over “blockade” to avoid the connotations of war and to garner full support from the Organization of American States. On the same day, Kennedy sent a message to Khrushchev stating that the U.S. would not tolerate the delivery of offensive weapons to Cuba and demanded the dismantling of the missile sites or their removal to the Soviet Union. This was the first of a series of direct and indirect communications between the White House and the Kremlin throughout the remainder of the crisis.

That evening, Kennedy addressed the nation on television, informing the public of the developments in Cuba, the existence of the missile sites, and his decision to impose a quarantine, emphasizing that any nuclear missile launched from Cuba would be considered an attack by the Soviet Union, necessitating a full retaliatory response. The Joint Chiefs of Staff raised the military readiness level to DEFCON 3, and the U.S. Navy began implementing the quarantine and accelerating plans for a potential military strike on Cuba.

On October 24, Khrushchev responded to Kennedy’s message with a statement denouncing the American quarantine as an act of aggression, asserting that Soviet ships en route to Cuba would be instructed to proceed. The crisis reached its peak that day when Soviet ships approaching Cuba neared the American naval quarantine line, raising the possibility of a military confrontation that could rapidly escalate into nuclear war. However, some Soviet ships turned back from the quarantine line, and others were halted by the U.S. Navy but allowed to proceed as they were not carrying offensive weapons. Meanwhile, American reconnaissance flights over Cuba indicated that Soviet missile sites were nearing operational readiness. With no clear end to the crisis in sight, U.S. forces were raised to DEFCON 2, indicating that war was imminent. On October 26, Kennedy informed his advisors that he was beginning to believe that only a U.S. attack on Cuba would remove the threat of the missiles but insisted on giving diplomatic channels more time. The crisis took a dramatic turn that afternoon when ABC News correspondent John Scali reported that a Soviet contact indicated that an agreement could be reached for the Soviets to remove their missiles from Cuba if the U.S. promised not to invade the island. While White House officials scrambled to verify the credibility of this secret channel, Khrushchev sent a lengthy, emotional letter to Kennedy that evening, evoking the specter of nuclear holocaust and proposing a solution similar to what Scali had reported earlier in the day. Khrushchev suggested that if there were no intention to bring about nuclear disaster, both sides should take steps to resolve the crisis, indicating readiness to do so.

Despite American experts being convinced of the authenticity of Khrushchev’s message, hope for a resolution was short-lived. On October 27, Khrushchev sent another message indicating that any proposed deal must include the removal of American Jupiter missiles from Turkey. On the same day, an American U-2 reconnaissance plane was shot down over Cuba, and its pilot, Rudolf Anderson, the only American combat casualty of the Cuban Missile Crisis, was killed. In response, Kennedy and his advisors prepared for a potential invasion of Cuba within days, by mobilizing an invasion force in Florida while continuing to seek any remaining diplomatic solution. Kennedy decided to ignore Khrushchev’s second message and respond only to the first. That night, Kennedy wrote a letter to Khrushchev proposing that the removal of Soviet missiles from Cuba be supervised by the United Nations, with guarantees against U.S. attacks on Cuba. Simultaneously, Attorney General Robert Kennedy secretly met with Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin and indicated that the U.S. planned to remove Jupiter missiles from Turkey anyway, but this would not be part of any broader resolution to the Cuban Missile Crisis. On October 28, Khrushchev publicly announced that Soviet missiles would be dismantled and removed from Cuba, and the crisis ended. However, the American naval quarantine remained in place until the Soviets agreed to remove their bombers. By November 20, 1962, the U.S. ended the naval quarantine, and American Jupiter missiles were removed from Turkey in April 1963.

The resolution of the Cuban Missile Crisis had significant repercussions. It enhanced Kennedy’s image both domestically and internationally and may have mitigated criticism of the failed Bay of Pigs invasion. Additionally, two major outcomes emerged: first, despite extensive direct and indirect communications between the White House and the Kremlin, the Kennedy administration and Khrushchev struggled throughout the crisis to clearly understand each other’s true intentions while the world teetered on the brink of nuclear war. To prevent a recurrence, a direct telephone link between the White House and the Kremlin, known as the “hotline,” was established. Second, after both superpowers came close to nuclear conflict, they began re-evaluating the nuclear arms race and took initial steps toward agreeing on a Nuclear Test Ban Treaty.